Servicemen named on the World War One Memorial in St Chads Church, part two

Date published: 04 November 2018

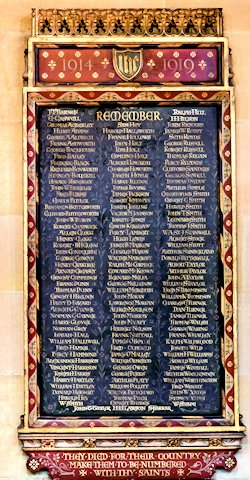

World War One Memorial in St Chads Church

In remembrance of those who fell during World War One, Rochdale Online is sharing the stories of those named on the St Chad’s memorial, so that others will never forget the sacrifice they made.

Reverend Mark Coleman said: “One of our congregation has been gathering photos and stories of those listed on the St Chad's war memorial.

“Many of the stories are very moving. The sheer scale of the loss of life is heart-breaking.”

Private William Snape

William Snape lived at 43 Cheltenham Street, Sudden, Rochdale with his mother and father. He worked at Whipp & Bournes Ltd, Castleton, a switchgear makers. William was a prominent attender at Rochdale Parish Church and the Sunday School, as well as being an enthusiastic member of 2nd Rochdale troop of Boy Scouts.

The Gordon Highlanders, like many other regiments, were recruiting in Lancashire. William’s friend, Percy Walton, had enlisted on 7 May 1915 in Bacup, Rossendale. William later joined him and enlisted in the same regiment. They were allocated regimental nos. S/10021 and S/13854 respectively.

The Gordon Highlanders were a regiment raised in 1794 by the 4th Duke of Gordon. Many of the first recruits came from the Gordon estates and wore a tartan similar to another Scottish regiment - the Black Watch. The Gordon Highlanders tartan had a yellow line added, as surprisingly, the Gordon family had no tartan of their own.

The sheer scale of the conflict in the First World War and the enormous demand for men transformed the Gordon Highlanders. Between 1914 and 1919, the regiment kept nine battalions on the western front. A battalion was between 300 and 800 men, sub-divided into companies. During the first world war over 50,000 men served with the regiment, which suffered 29,000 casualties of which some 9,000 died in action.

Private William Snape was killed at the Somme in France on 23 July 1916. He was age 21. His parents were initially informed of his death by his friend Percy, also from Sudden. Percy was killed on the 17 August 1916, also at the Somme. He was 20 when he died.

It is not known where either soldier fell, and both are commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial.

Private Alfred Moulson

Born in Manchester, the census for 2 April 1901 lists Alfred Moulson as living with his family at 10 Grape Street in the electoral ward of St Johns, Manchester. The family included his father Edwin, described as a lodger, and his mother Hannah, along with Alfred’s siblings Edwin, aged 18, William, 16, and Herbert, 13. There are two other families described as lodging at the same address.

Alfred’s mother died in March 1904, followed by his father’s death in December 1909. Subsequently, Alfred was placed in ‘The Home for Waifs and Strays’ on Castlemere Street, Rochdale. The home opened in 1891 and took children in from all parts of Britain, initially taking in five boys who had previously lived in the local workhouse. Boys were accommodated at the home from the age of 8 until they were 12.

On 23 December 1911, Alfred aged 13, sailed as a passenger of the White Star Liner, the SS Waimana, from Liverpool to Australia. His occupation in the passenger list is described as a ‘messenger’. When he arrived in Australia, it is believed Alfred went to live with his sister Ada Sharples in Perth. At the start of the war, he enlisted in the army in Perth where he described his sister as a sibling and his next of kin.

Alfred Moulson was a private in the 51st Battalion of the Australian Infantry.

Australia and New Zealand had rallied to the Allied cause and sent thousands of troops to Europe to fight against the Ottoman Empire in present day Turkey. The Australian 51st Infantry Battalion was sent to the Somme in north-eastern France.

Alfred was killed at The Battle of the Somme on 4 August 1918, aged 20. He is buried at Domart-Sur-La-Luce Communal Cemetery, between Amiens and Roye. The records of his burial detail his parents as Edwin and Hannah Isabella, matching with those on the 1901 census.

Private Alfred Moulson is recorded in the Western Australian State War Memorial in the Undercroft in Kings Park, Perth.

Midshipman Donald Stewart Tattersall

Donald was born in Rochdale in 1898. In his teens, he moved to Lytham with his parents, Arthur and Louise J. Tattersall, where they lived at 3 Blackpool Road, Lytham St Annes, ‘Oakenrod’.

In September 1912, Donald, age 14, joined the training ship HMS Conway where he spent 2 years, hoping for a career in the Royal Navy.

HMS Conway was a training school founded in 1859 and was housed for most of its life aboard a 19th century wooden hulled ship of the line. The HMS Conway was commissioned in May 1832 and was wrecked in 1953.

After leaving HMS Conway Donald joined the Navy and after initial training, was posted to HMS Formidable as a provisional midshipman – a trainee deck officer.

HMS Formidable was a ‘pre-dreadnought’ battleship, sunk in the English Channel in the early hours of 1 January 1915. Formidable was the first British battleship and largest warship at that time to be sunk by a German submarine.

Six battleships sailed from Sheerness at 10am on 29 December 1914, accompanied by a number of destroyers, with the intention that the battleships should practice their gunnery. The sea conditions were rough with poor visibility and a number of destroyers were forced to return to port. The remaining destroyers were unable to protect the fleet and the HMS Formidable.

A German submarine that had been shadowing them, commanded by Kapitän Rudolf Schneider of the U24, was able to fire two torpedoes which hit the Formidable. The battleship sank immediately, with the loss of over 500 lives.

Midshipman Donald Stewart Tattersall, Royal Navy, was just over seventeen years old when he died.

Naval technology and engineering had made huge advances since the building of the Formidable class at the turn of the century. A new class of battleships began to appear in 1906, with the building of HMS Dreadnought. These vessels were driven by steam turbines and had four screws giving them top speed of 21 knots. The ships were also equipped with more powerful guns, rendering the earlier vessels, including the Formidable, almost obsolete.

Private Henry Crabtree

Private Henry Crabtree was born in Rochdale in July 1879 and immigrated to Canada in 1904, aged 25. His mother remained in Rochdale, living at 8 Prince Place, Prince Street, Rochdale.

Canada offered to help the Allied cause and sent troops to France in August 1914. Henry Crabtree enlisted in the Canadian Army in the Eastern Ontario Regiment on 23 October 1914. His regiment was sent to Belgium in 1915, along with another Canadian regiment the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry.

Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry was founded by Andrew Hamilton Gault, the son of an English textiles millionaire whose family lived in Montreal, Canada. Gault had signed up to fight in South Africa in 1901 whilst Britain was fighting in the Boer War. When war was looming in Europe, Gault had written to the Canadian government in Ottawa, offering to spend $100,000 (Canadian) to recruit and train a regiment. The Canadian authorities accepted his offer.

This regiment was named Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry after Patricia, the daughter of the Canadian Governor General, the Duke of Connaught. In the first ten days, the new regiment had recruited 1,008 soldiers.

Known as ‘The Originals’, most had served with the British Army before immigrating to Canada. The regimental history describes these recruits as “prospectors, trappers, guides, cow punchers, prize fighters, farmers, professional business men and above all… soldiers.” The regimental colours known as ‘The Ric A Dam Doo’ was, and still are, blood coloured. The colours were sewn by Princess Patricia herself as a gift to the regiment. The motto is said to be from the Gaelic phrase the ‘Cloth of our mother’.

In 1915, the regiment was sent to France and then on to Ypres, Belgium where they were in the trenches with French troops near St Eloi. The regiment suffered ‘massive’ casualties in a battle near Frezenberg in Flanders.

On 7 May 1915, the regiment’s active strength was whittled down from 700 to 150. The Princess Patricia’s losses were replaced by other Canadian troops, including Private Crabtree. The record of the Canadian Army revealed what happened:

‘Crabtree, Harry Private 51122. Born in Rochdale, Lancashire, England July 1879. Served with 2nd Lancashire Fusiliers (volunteers). Employed as a moulder before joining 23rd Bn 23 Oct 1914. Became a member of the Patricia Reinforcements in January 1915 and joined PPCLI in the field in the St. Eloi Sector 11 March 1915. He was listed killed five days later on 16 March 1915.

The enemy assaulted and captured the mound at St. Eloi during the same evening. They were to attack and recapture the area West of the Mound in concert with the 4th Battalion Rifle Brigade in the early morning of the 15th.

The attack was cancelled after Lt.-Col. Farquhar surveyed the scene after the initial foray towards the German positions. Casualties during this manoeuvre were, Lt. Cameron killed along with seven NCOs and men killed. Pte Crabtree aged 35, was among them. Another two officers and seventeen ranks were wounded.’

As the records above relate, Private Crabtree had been a moulder before he immigrated in the early 1900’s. He had also served as a volunteer in the Lancashire Fusiliers in 1902 in the Boer War in South Africa, mentioned in the above extract from the records.

Private Crabtree is buried at Voormezeele Nc. Cemetery, Belgium.

The Patricia’s still exist today and have seen recent service in Afghanistan.

Private Frank Dunn

Frank Dunn lived at 25 School Lane, Rochdale. He worked as a turner at David Bridges Ltd, an engineers in Castleton, and was a keen sportsman playing for St Johns Roman Catholic Football Team. The team played in the Rochdale Association Sunday School League.

Private Dunn, Regimental no. 10459, joined the Territorial Army, enlisting in his local regiment The Lancashire Fusiliers in 1914. The fusiliers, together with other regiments of the British, Commonwealth and French armies, were sent to Dardanelle Straits in Turkey in 1915.

The Ottoman Empire (now Turkey) had entered the war on Germany’s side and Russia had entered the war on the side of the Allies. The Allies wished to supply Russia with armaments, but couldn’t supply them by the Baltic, nor via Archangel, as the Germans had control of the Baltic and there were U-boats in the North Sea. The only other route was through the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, which had to be accessed via the narrow straits of the Dardanelles.

To achieve this strategy, the Allied High Command wanted to attack the Turkish capital Constantinople, hoping this would force Turkey to cease their support for Germany. The Allies would then be able to supply Russia through the Aegean Sea, the Dardanelles and the Black Sea.

The Germans appreciated the importance of this strait and had sent officers to advise the Ottomans.

The Royal Navy and the French bombarded the Turkish forts at the entrance to the Dardanelles, but this action did not remove the forts. It was then decided to launch a land invasion with troops from both Britain and France. The French attacked the Asian (southern) side of the Dardanelles and the British and Commonwealth troops attacked the Gallipoli peninsula.

There were a number of landings by the British, Australian, New Zealand and Indian troops. The Australian and New Zealand landings on 25 April 1915 at Anzac Cove cost 700 Australian and New Zealanders their lives.

The same day, the Lancashire Fusiliers were part of the British landing at Helles beach. The Allies named this beach ‘W’. In this battle, over 700 fusiliers’ men were killed or wounded. The action by the Lancashire Fusiliers resulted in the regiment being awarded six Victoria Crosses for their involvement.

The Allies had not penetrated as far inland as they had hoped. Between April and August, both sides reinforced their forces, with the Allies increasing their troops from 5 to 15 divisions and the Ottomans increasing theirs from 6 to 16 divisions.

The amphibious landings at Suvla Bay on the Aegean Sea were intended as a fresh attack to break the deadlock in the Gallipoli campaign. Suvla Bay has been chosen, as the Helles beach did not have sufficient space to safely land all the troops.

On 6 August 1915, the landing at Suvla Bay went ahead but the Allies did not push inland as far as had been hoped. The Ottomans occupation of the Anafarta Hills prevented the Allies penetrating further inland.

Private Frank Dunn was killed on 7 August 1915, age 24. He has no known grave.

Private’s Dunn’s name is engraved on the Helles Memorial, Turkey, panel 58 to 72.

Lieutenant Norman Grey

Norman Grey was born on 20 November 1883, the son of John and Minnie Grey. He was baptised at St Paul’s Church, Norden on 28 January 1894. Norman was educated at Rochdale Collegiate School and Rochdale Technical School. He also worked as a clerk.

In August 1915, he joined the Inns of Court Officer Training Corps. He was gazetted as a 2nd Lieutenant, joining the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment on 12 January 1916. Promoted Lieutenant in August 1917, Norman served with the British Expeditionary Force in France.

At the start of the war, the German troops arrived in Ypres in northern Belgium, near the border with France. The Allies were determined to stop the Germans advancing beyond Ypres and taking the channel ports of Calais and Dunkirk. There was continuous fighting around Ypres for all of the war and the town was completely destroyed in these battles.

The Loyal North Lancs. Regiment was involved in the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as the Battle of Passchendaele, in 1917. The recent fighting had been a costly failure with the troops back at starting point. The British commander, Douglas Haig, was convinced that a crucial break through was imminent.

There were no fresh British, Australian, or New Zealand divisions available – Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig, senior officer of the British Army, turned to the Canadians for troops for the fresh attack. He believed the war could only be won on the Western front. General Sir Arthur Currie, commanding the Canadian troops, was reluctant to get involved in what he considered would be a bloodbath; he predicted the attack would cost him 16,000 casualties.

It had rained every day since 19 October and the troops already in the field were hindered by the extreme weather. The Loyal North Lancashire Regiment’s diary records their attack. An extract from the Battalion’s War Diary states:

‘Throughout the 25 October the Battalion held the line under the very worst possible conditions of rain and mud, the enemy keeping up a heavy if intermittent shelling, which cause fifty-three casualties; and about 5 o’clock in the morning of the 26th, the companies formed up to attack an objective which was distant about 1000 yards from the original line.

‘At 5.40 the Battalion moved off in attack formation, three companies being held in the front line and one being held in the readiness as a counter-attack company, each platoon having a frontage of about 160 yards. The “going” was almost impossible, but the men pushed on steadily if slowly.

Owing to the state of their weapons it was practically impossible to use either rifle or Lewis gun, and the men had to give trust to the bayonet, in the wielding of which the men of the accounted for some five hundred of the enemy and captured eight machine guns. One sergeant attacked and killed the detachments of two German machine guns single-handed and was still advancing when he himself became a casualty.’

It was on this early morning, 26 October 1917, that Lieutenant Norman Grey died. Another 100 officers and men of the L.N.L Regiment were also killed in the same attack. Grey’s commanding officer wrote: “It is with sadness I write to inform you that your son was killed while gallantly leading his platoon in the first wave of the attack. The fighting was most bitter, and the conditions were bad. I have lost a good young officer”. The adjutant wrote in a separate letter “…the men thought the world of him.”

General Sir Arthur Currie’s prediction of the outcome of the attack was accurate. The Canadians suffered 15,634 casualties, 4,000 dead and 12,000 wounded.

Lieutenant Grey is buried at Poelcapelle British Cemetery, Belgium. There are 7,478 Commonwealth soldiers buried here too and of those burials, 6,231 are of unidentified servicemen.

2nd Lieutenant Alexander Harrison

Alexander Harrison was the youngest son of Robert and C M Harrison of 59 King Street East, Rochdale. He joined the Royal Flying Corp (RFC) as a flight cadet with the service no. 100046. Applicants for aircrew generally entered as a cadet.

On 1 April 1918, the Royal Flying Corp (RFC) merged with the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) to form the Royal Air Force (RAF). After starting with 2,073 men in 1914, by the end of 1918 the RAF had 4,000 combat aircraft and 114,000 personnel in some 150 squadrons.

When it was established, the RFC needed to develop a program for training pilots. After three years of the war in 1918, this had developed into several phases that a prospective pilot must achieve in order to eventually gain their wings. This began with basic military training lasting two months and included drill, physical training, map reading and signalling in Morse code.

They then moved onto the School of Military Aeronautics for two months of military training and ground instruction. This included aviation theory, navigation, map reading, wireless signalling and using Morse code, photography, artillery and infantry co-operation. They were instructed in the working of aircraft, instruments and the rigging of a plane.

The next stage of instruction was at a Training Depot Station (TDS), here the cadets received 25 hours elementary flying training both dual and solo in an Avro 50. This was logged over three months and there was thorough ground instruction. Cadets who achieved this were given a Grade A.

Staying at TDS, there was a second phase lasting two months and involved a further 35 hours of flying with a minimum of five hours in a modern ‘front line’ type of aircraft. It was required that cadets demonstrate proficiency in cross country and formation flying, reconnaissance work and gunnery. Successful candidates were graded B and commissioned.

In 1918, it was taking a total of eleven months to qualify as a pilot. Once qualified, the typical life expectancy in combat could be only as short as several weeks. In flying hours, this was between 40 and 60 hours.

Alexander Harrison was gazetted as a Second Lieutenant only one month before his death on 5 July 1918. ‘Gazetting’ was the way that promotions in the services were formally announced in the London Gazette.

Alexander was killed in a flying accident over Southern England, aged 18 years old. He is buried in Manchester.

2nd Lieutenant William Alexander St John Stanwell

William Stanwell was born in 1894, the only son of Dr William and Mabel Frances Stanwell of Wellington Terrace, Rochdale. He was baptised at St Mary’s in the Baum, Wardleworth on 25 July 1894.

Educated initially at Mr Robinson’s Castleton Hall School, he then went to Blundell’s School in Tiverton, Devon. There, he was in the Officer’s Training Corps for five years. On leaving school, he enrolled at Guys Hospital as a medical student where he studied until August 1914. He joined the Artists Rifles as a private at the outbreak of war and was sent to France in October 1914. On returning, he was awarded a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 3rd Lancashire Fusiliers, 2nd Battalion.

2nd Lieutenant William Alexander was killed on 9 July 1915 at Pilkem in Flanders, Belgium to the north of the town of Ypres. The Allies were trying to push the Germans back from the Yser canal as they were determined to prevent the Germans taking Ypres, which would have given them access to the Channel Ports.

Williams regiment and others had been sent to the front near to Boezing, north of Ypres. This village has its place in history as the site of the first large gas attack in military history, on 22 April 1915. The Germans released 168 tons of Hypochlorous acid, which destroys lung and eye tissues. The French sustained 6,000 casualties dead or wounded from this attack. The British suffered 350 dead from the gas.

The gas attack allowed the Germans to advance westward from Langemark, the nearest village to the east from Boezinge in the northern part of Ypres, salient in present day Belgium.

The German army advanced from Steenstate to Boezinge and up to the Yser Canal where they managed to cross for a short while. The canal acted as a natural boundary with the French on the left bank and the Germans on the right. The Germans planned to break through the Allied line, which at first consisted of French troops. British and Canadian troops reinforced the French to prevent the German advance.

Various British regiments were involved in the later battle following the gas attack, the Shropshire Light Infantry, the East Lancashire Regiment, the Hampshire and the Rifle Brigade. From 6 July to the 9 July, there was a violent battle between the German and British troops from the Royal Warwickshire Regiment, the Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry and the 2nd Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers.

It was during this violent battle that 2nd Lieutenant Stanwell was killed. He was aged 21. He is commemorated at Kings College, London, the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres and St Chad’s, Rochdale.

-------------------------------

Before the First World War, widows of men killed in the war had to rely on charities for their financial support. The loss of life in the First World War was so great that provisions had to be made by the state to care for war widows and their dependent children. The need had been identified in the first two years of the war.

A new department, the Ministry of Pensions, was founded in 1916 to deal with the provision of pensions for war widows and claims by injured soldiers who had disabilities. This fundamental change created a safety net for soldier’s wives.

However, if a servicemen was only ever posted as 'missing', his wife could never be declared a widow, therefore they could not receive a war widows pension.

Do you have a story for us?

Let us know by emailing news@rochdaleonline.co.uk

All contact will be treated in confidence.

Most Viewed News Stories

- 1The plan for two new apartment blocks with an unusual car parking system

- 2Andy Burnham responds to harrowing reports from hospital nurses

- 3Police seize £48,000 in Rochdale property search

- 4The museum undergoing £8.5m transformation now needs a new roof

- 5Residents urged to be vigilant after spike in Shawclough burglaries

To contact the Rochdale Online news desk, email news@rochdaleonline.co.uk or visit our news submission page.

To get the latest news on your desktop or mobile, follow Rochdale Online on Twitter and Facebook.