Servicemen named on the World War One Memorial in St Chads Church, part one

Date published: 03 November 2018

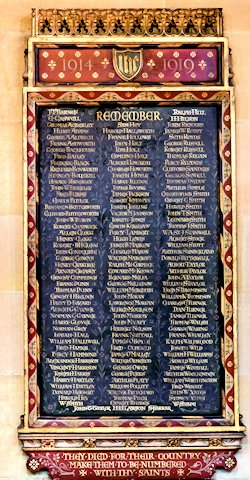

World War One Memorial in St Chads Church

In remembrance of those who fell during World War One, Rochdale Online is sharing the stories of those named on the St Chad’s memorial, so that others will never forget the sacrifice they made.

Reverend Mark Coleman said: “One of our congregation has been gathering photos and stories of those listed on the St Chad's war memorial.

“Many of the stories are very moving. The sheer scale of the loss of life is heart-breaking.”

Lieutenant Horace James Brierley

Born in Rochdale in 1890, Horace James Brierley was the child of Roger and Catherine Brierley, and lived at 104 Tweedale Street. He was baptised at St Chad’s Church on 15 March 1890. As a child, Horace was educated at Rugby School, Warwickshire, before entering New College Oxford in 1909 where he read law. He was Called to the Bar, the Inner Temple, in 1914.

With war looming, Horace joined his local regiment, The Lancashire Fusiliers, as a Lieutenant and was posted to the 9th (Service) Battalion, formed in Bury on 31 August 1914. This was part of the ‘New Army’ and moved to Belton Park, near Grantham, to join the 34th Brigade.

The Allies had plans for a combined naval and army expedition, proposed by Winston Churchill, to attack and seize the Gallipoli peninsula in early 1915 and attack Constantinople. The Allies wished to stop the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) from supporting the German side. They wanted to supply arms and equipment to the Russians who had entered the war on their side. The proposed supply route was through the Dardanelles Strait.

The campaign was fought from 25 April 1915 to 9 January 1916 and was the first amphibious operation in modern warfare. The allied troops landed in Turkey on the peninsula in the Dardanelles Straits with disastrous consequences. The Turks had defended the straits with minefields, fortifications and gun emplacements on the peninsula. The naval bombardment alerted the Turks to the pending attack and any allied landing had now lost the element of surprise. To make matters worse, the badly planned invasion lacked landing craft and the troops had little training in this type of operation or warfare.

The French attacked the Asian (southern) shore of the Dardanelles as a diversion on the 25 April 1915. The Australian and New Zealand forces attacked a bay on the coast at dawn, facing the Aegean Sea now called Anzac Cove. The British attacked Cape Helles with its well defended positions and barbed wire, suffering appalling casualties. Of the first 200 men, only 21 made it to shore.

It was in this battle that the Lancashire Fusiliers were awarded 6 Victoria Crosses. In total, 700 Fusiliers were killed or wounded on the beach that day.

The 34th Brigade then mobilized for war in July 1915. They sailed to Alexandria in Egypt, then onto Imbros in Turkey. One can only imagine the thoughts of the men as they sailed to Turkey, knowing of the previous horrendous loss of life. The Brigade landed at Suvla Bay on the 6 August where they took part in the Battle of Scimitar Hill.

The History of the Lancashire Fusiliers Vol.1 1914-1918, page 89, details Lieutenant Brierley’s involvement in the action after other officers of the regiment had been killed.

Lieutenant Horace James Brierley was killed on 7 August 1917.

The number of casualties in the unsuccessful Dardanelles campaign is frightening. 747 Australians died on the first day at Anzac Cove. A total of 44,070 allied troops were lost, including 8,709 Australians. Over 90,000 allied troops were injured. The campaign was eventually abandoned.

2nd Lieutenant Benjamin Butterworth

Benjamin Butterworth was the second son of Alexander and Elizabeth Butterworth of 45 Walpole Street, Rochdale. He was baptised on 3 July 1889 at St Chad’s Church and attended the Parish Church Sunday School. The family later moved to 429 Bury Road.

When he was 14 and a half, Benjamin was apprenticed to Messrs. Carter Bros (Rochdale) Ltd as an engineer for four and a half years. He gained the Science Exhibition Prize of £150 given by Messrs. Thos. Robinsons and Sons Rochdale, entering Manchester University in 1910 to read Mechanical Engineering.

While at university, he was in the University Officers Training Corps from 1911 to 1914. On graduating, Benjamin joined the 3rd Battalion the Manchester Regiment as a Second Lieutenant. He was gazetted on 17 February 1915 and later sent to Mesopotamia, now Iraq.

In 1908, oil had been discovered in the Persian Gulf. A British company - the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) - had been established in the same year, issuing a prospectus in 1909. The company moved quickly to exploit the oil and built a 145-mile pipeline that connected the oil lines in Persia with a refinery they were building on Abadan Island, close to the mouth of the Shatt al Arab. The pipeline was a major engineering project and involved the building of pumping stations. In 1912, the first shipment of oil left Abadan on a ship owned by Royal Dutch Shell. The refinery built at Abadan was later to be the largest in the world.

By 1914, the APOC had signed a deal with the Royal Navy for the navy to take 40 million barrels of oil a year for 20 years. The UK government took a large take in APOC to safeguard this oil supply. The world oil industry was then largely in the hands of the United States.

Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, was dedicated to safeguarding a guaranteed supply of this ‘new fuel’ for warships as it had better energy density, allowing a longer steaming range for the same bunker capacity. Others in the admiralty had wanted coal to still be the Navy’s principal fuel.

The Ottoman Empire (Turkey) sided with Germany in the war and the British considered it essential to have a powerful presence in the region to protect this new fuel and their investment. Britain dispatched troops to the area of the Persian Gulf, specifically to protect their interests in the oil. The troops consisted of British, as well as a large contingent of Indian troops including the 6th Poona Regiment. These troops eventually captured Basra in November 1914 and having taken Basra, the British then pushed on North towards Baghdad.

The regiment was in action near to Kizil Rolat when 2nd Lieutenant Butterworth was wounded. He died of these wounds on 17 March 1917. He has no known grave.

Benjamin’s name is inscribed on the War Memorial that stood on the main quay of the dockyard in Maqil, in present day Iraq. The memorial was relocated in 1997, alongside the road to Nasiryah at the site of a major battle during the 1st Gulf War. Considerable manpower and transport costs were incurred in moving this large structure by Iraq. Luckily, the memorial with Lieutenant Ben Butterworth’s name carved in purple slate survived.

Gunner Edwin Butler

Edwin Butler lived with his wife at 7 Norman Road, Rochdale. He worked as a carter for Messrs S. Heap & Sons, Caldershaw Mills, Spotland, who were dyers, fullers and finishers of cloth. He attended St Clements Church, Spotland.

Edwin enlisted, aged 27, and was allocated to the Royal Field Artillery in October 1915, Regimental no. 113897. The role of the Royal Field Artillery was to provide close support for the infantry on the battlefield.

On 13 October 1914, German troops arrived in Ypres. The British and French forces wanted to deny the Germans access to the Channel ports of Dunkirk and Calais. Having arrived first, the Germans occupied the higher ground near Ypres; its height giving them the advantage in controlling the surrounding area.

Gunner Edwin Butler and countless other British and French soldiers were sent to the Belgian town of Ypres, close to the French/Belgian border and just inland from the Channel coast. The fighting continued around Ypres for the duration of the war and the town was completely destroyed. One side making gains, which the other then recovered at massive costs in lives.

Between 31 July and 10 November 1917, there was continual fighting known as the Battle of Passchendaele. The Allies initially began by making encouraging gains, but that year there was a terrible summer with rain that resulted in the men and equipment becoming bogged down.

By August, the allied advance was clearly failing in its objective and the action descended into attrition fighting between the two sides, who both suffered enormous losses.

Gunner Edwin Butler was killed on 8 August 1917 during this series of battles. He is buried at Brandhoek New Military Cemetery in Belgium, near Ypres. His brother in law Sam Smith, number 27023, was a private in the Border Regiment. He was also killed in May 1917.

Private Robert Chadwick

Robert Chadwick was the son of John and Sarah Chadwick of 38 Church Lane, Rochdale. He was baptised at St Chad’s Church on 13 September 1876.

Before enlisting in 1914, Robert worked at Thomas Robinson & Sons Ltd on Fishwick Street, Rochdale as an iron driller. Robinsons made woodworking and floor milling machinery. Chadwick was married and lived with his wife Ada and their five children aged 16, 14, 10, 9 and 6 at 17 Holroyd Street, Rochdale.

Robert was a well-known local sportsman and had captained Rochdale Rangers Football Club for a number of seasons.

Robert enlisted at the start of the war and was allocated to the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry, the 5th Battalion, Regimental no. 15005. In the war, some ‘county’ regiments had difficulties getting numbers of men to fill the ranks, and it sometimes happened that men enlisting found themselves being sent to regiments some distance from their homes. It is assumed this is how a Rochdalian found himself in the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry.

A Light Infantry Regiment traditionally carried lighter weapons and equipment. They had been trained to fight in smaller groups unlike the massed ranks of normal infantry. The concept of light infantry had been used less, as the difference between ‘light’ and normal infantry disappeared. The word ‘light’ has been retained by the ‘Shropshires’ and a number of other regiments.

Private Robert Chadwick was officially reported missing on 25 September 1915, at the age of 39. He had been in Belgium since May of that year. His regiment, together with others, were in trenches near Ypres in Belgium, both north and south of the Menin Road.

The Shropshire Regimental Museum records the 5th battalion’s involvement as: “On the 25 September the battalion was relived by a Yorkshire battalion. On their way back to bivouac, the company was shelled losing two other ranks with 12 wounded.” His commanding officer said that Private Chadwick had “last been seen throwing bombs at the German lines”. It was at first thought that he had been wounded or taken prisoner.

Private Chadwick has no known grave and is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial and at St Chad’s.

Private Percy Hammond

Private Percy Hammond was the son of Mr and Mrs Hammond of 89 Tweedale Street, Rochdale. He was employed by Messrs W. Standring Ltd, Bury Road, Rochdale who made industrial springs.

Percy enlisted in the Lancashire Fusiliers on 20 January 1916, regimental No. 28433, and was sent to France on 20 June 1916 with other members of the 11th Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers.

The first German offensive, now known as the ‘Schlieffen Plan’, had not achieved its aim of delivering a winning offensive against the 3rd French Republic. There were trenches from the Swiss border to the North Sea, with both sides bogged down. The German army had attacked Verdun to the south of the Somme and the French commander Joffre wanted the British to attack the Germans earlier than the British would have wished.

The Allies decided to try to remove the Germans from a 24-kilometre section of the Somme River in northern France. The battle that ensued was to become one of the major battles of the war and lasted from the 1 July 1916 until 18 November 1916.

The scale of the slaughter still is quite staggering.

On the first day, 100,000 men were sent ‘over the top’. The British army comprised mainly of volunteers, with little battle experience or training. There had been an artillery bombardment of the German trenches. This did not have the desired effect as the Germans were in deep trenches.

The British were attacking German trenches manned by battle hardened soldiers with a large number of machine guns. On 1 July 1916, the British lost 19,240 men and over 38,000 were wounded. In total, the British and Empire troops suffered one million casualties with 300,000 killed or missing. The Allies had problems with their equipment; some of the thousands of shells fired were duds and some of the bombardments before the battle were off course.

The Somme saw the first use of ‘tanks’, so called because they resembled water tanks. They were slow with a maximum speed of 4mph and many also broke down. Despite the aims and the immense loss of life, the maximum advance by the Allies was a mere five miles.

On 10 August 2016, 100 years after the battle, 20 million (almost half of the population) watched a film ‘The Battle of the Somme’ on the television.

The offensive was stopped more by the calendar and the pending winter than the generals.

On 16 July, Private Hammond was reported missing at the Somme. He was aged 19. He, like thousands of others, has no known grave. He is commemorated in the Connaught Cemetery, Thiepval.

In the area around Thiepval, more than 72,000 British and South African troops are commemorated. He is not the only man on the St Chad’s memorial to have died at the Somme.

Reverend Henry Heaton Lawson

Henry Heaton Lawson was born in 1888, the son of William Henry Lawson, the headmaster of a local church school.

Educated at Rochdale Higher Grade School, Henry entered Manchester University in 1907 and was awarded a BA in 1910 and an MA in 1911. His first teaching appointment was at Woodhouse Secondary School, near Sheffield and one year later he moved to Rutherford College, Newcastle upon Tyne.

Whilst a teacher, Henry wrote a book on the study of the English Language and completed work on elementary Latin. He was a founder member of his school’s old student’s association and was its first secretary.

After a year in Newcastle, Henry Lawson left teaching in order to enter the ministry, enrolling at Ripon Theological College. He was ordained at Ripon Cathedral in 1914. His curacy was at St Andrews Stourton, Hunslet, near Leeds.

In August 1916, he married Hettie Earnshaw, the eldest daughter of James Earnshaw of Bacup, Lancashire and they had a daughter. In late 1916, Henry resigned from his curacy and enlisted in the Inns of Court Battalion (OTC) at Berkhamstead, Herts.

Commissioned into the army as a chaplain, in July 1917 Henry went to France as the chaplain to 2nd Battalion of the Northamptonshire Regiment and the 8th Battalion Sherwood Foresters. He returned to England on leave at the end of 1917. On his return to France, he was with the 1st Battalion of the Lancashire Fusiliers.

On the 24 March 1918, Reverend Henry Heaton Lawson was killed instantly by a shell after returning from visiting wounded men. He is buried in the Fouquescourt British Cemetery. The senior chaplain of his division wrote: “It is not too much to say that in him we have lost one of our keenest and best men, who was liked and respected by all who knew him.”

The Army Chaplain’s department did not have the usual system of officer’s ranks, but Reverend Lawson was a Chaplain 4th class and this rank was effectively that of a captain.

The action in which Henry died was one part of a major German Spring Offensive named ‘Operation Michael’, which began from the Hindenberg Line near Saint Quentin in France. The German Army had been re-enforced by troops who had previously been fighting on the Russian Front, after the Russians ceased fighting. This allowed Germany to move troops from the east to the war in France. The German high command believed that their best chance of victory was before the American troops began to arrive in large numbers - they launched this Spring Offensive as ‘a last throw of the dice’.

The Allies, including some American troops, were able to beat back this attack. The failure of this offensive marked the beginning of the end of the First World War for Germany.

The blockade of Germany imposed by the Allies had started to affect Germany, which was experiencing severe shortages of food. Germany didn’t have sufficient agricultural production to feed both its army and civilian population and were also short of materials and were running out of ammunition. Another factor that weighed in the Allies favour was that in early 1917, the Americans had entered the war on the Allies side. By 1918, they were contributing 10,000 fresh troops a week to help the Allied cause.

Do you have a story for us?

Let us know by emailing news@rochdaleonline.co.uk

All contact will be treated in confidence.

Most Viewed News Stories

- 1The plan for two new apartment blocks with an unusual car parking system

- 2Andy Burnham responds to harrowing reports from hospital nurses

- 3Police seize £48,000 in Rochdale property search

- 4The museum undergoing £8.5m transformation now needs a new roof

- 5Residents urged to be vigilant after spike in Shawclough burglaries

To contact the Rochdale Online news desk, email news@rochdaleonline.co.uk or visit our news submission page.

To get the latest news on your desktop or mobile, follow Rochdale Online on Twitter and Facebook.